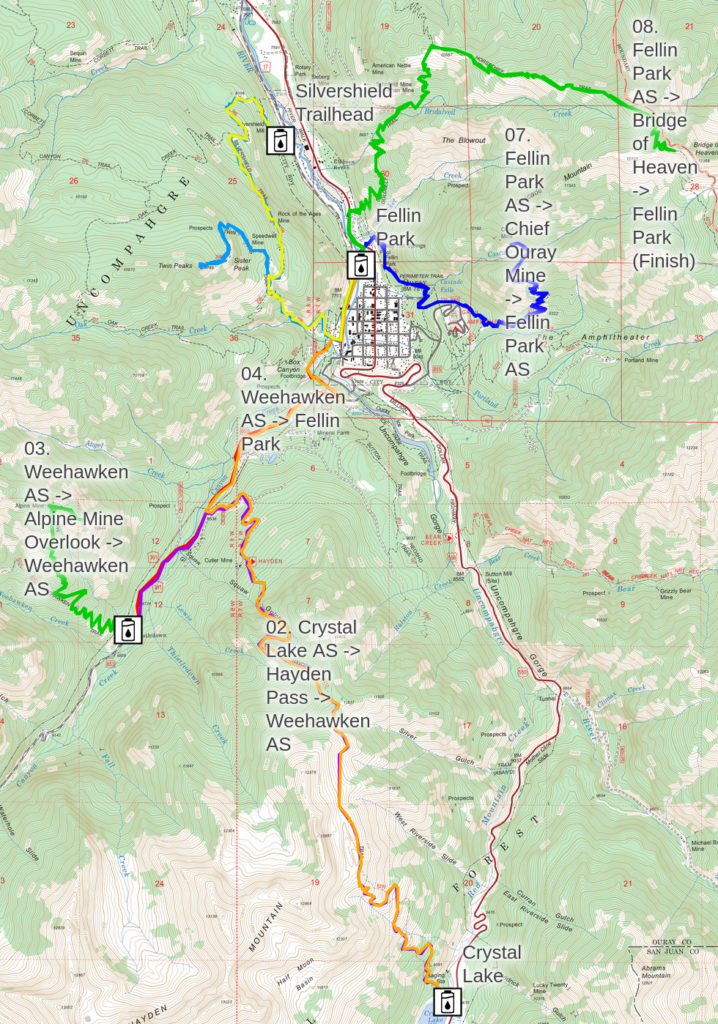

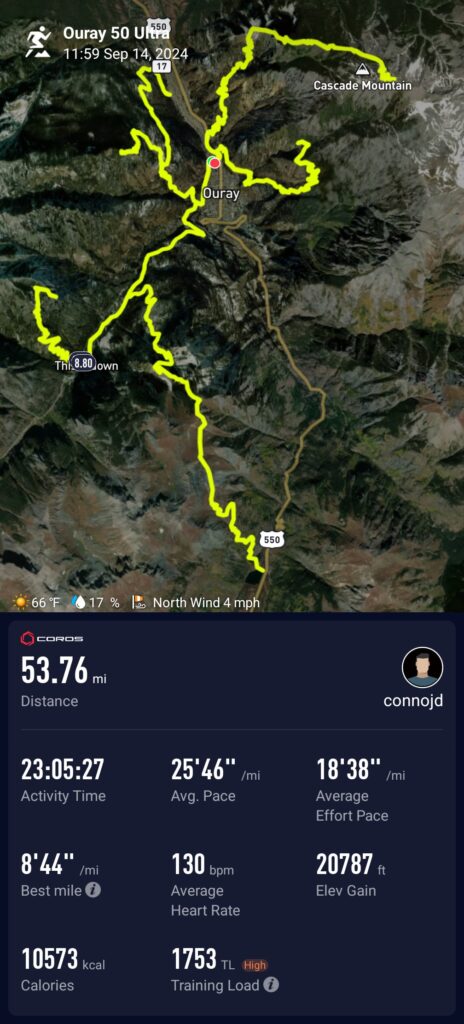

I had the opportunity to participate in the Ouray 50 ultramarathon in September. The Ouray 50 is kind of insane. Runners have 24 hours to run 50 miles1 with over 20,000 feet of elevation gain around the historic mining trails of Ouray in southwest Colorado.2

This was the second ultra I’ve done in my life. I can’t really describe why I decided to do arguably the most difficult 50-miler in the ultramarathon world as my second-ever race (the first I did was a 50k). It was more of a gut feeling that I should do it rather than the result of calculated decision making. A call to adventure, if you will.

Training

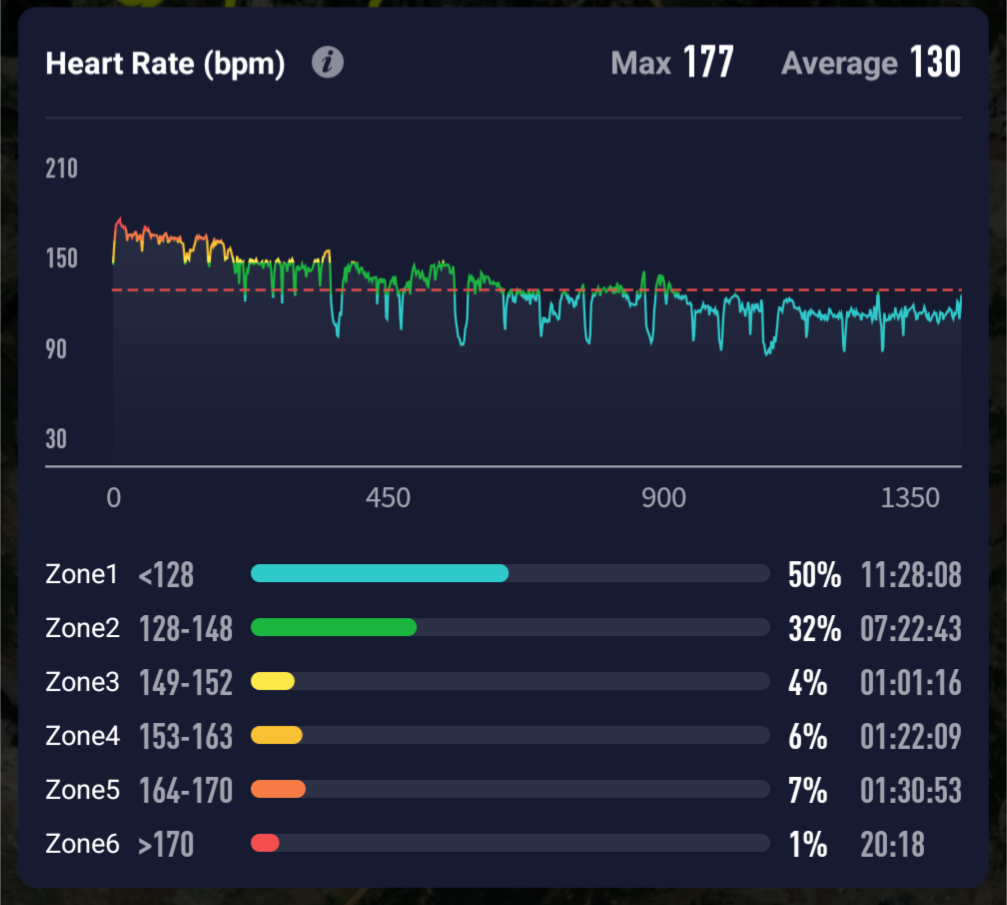

I started training for the race in March of this year. I focused on building out my aerobic base from March until about mid-July. This consisted of high volume, low-intensity runs, in addition to maintaining a fairly regular schedule at my gym for strength and mobility. My goal for each run during this period was to stay under (within 10 beats of) my aerobic threshold for the entire run. About two months out from the race, I shifted focus on elevation and strength training. I trained on the trails around Ouray, doing 6 to 9 hour days on the weekend.

As you can see from my Garmin data above, my highest average distance during training was around 25 miles per week. There were a few runs that I didn’t have my watch on, but not enough to have put me much over the 25 miles per week mark, if at all. Since I’m not a professional runner by any means, my goal was just to finish before the 24-hour cutoff. I didn’t have much more time to train given my job, social responsibilities, and other hobbies. I didn’t follow any formal training plan or coaching.

Despite the lack of a formal training regimen, I did follow the recommendations from Mark Sisson’s book, Primal Endurance. One key argument of the book is that endurance athletes tend to overtrain and underrecover. This is especially easy to do when you already have good fitness and you are following a strict training schedule that only focuses on volume. The book shows that subjective feelings of rest aren’t necessarily sufficient to determine your recovery level. Instead, you need to measure heart rate variability (HRV) and combine that with how you feel. A lower HRV means you should probably rest more before the next training session. During my own training, there were many mornings where my body felt good, but my HRV was in the ditch, so I ended up taking extra rest days until my HRV recovered to baseline or better.

The other major lever I used to train had nothing to do with exercise: nutrition.

Nutrition

I’m an ardent reader of Lyn Alden’s investment research. Her macro takes are probably the most clear and well written economic analysis I’ve ever read. She also has a fantastic book called Broken Money. Read it. Take notes. Everyone should read that book.

You’re probably wondering, what the hell does Lyn Alden and investment research have to do with my nutrition for the Ouray 50? Well, she has a non-financial article called 12 In-Depth Tactics to Seriously Boost your Energy that I happened to read in May, espousing the benefits of low-carb ketogenic diets for mental and physical performance. In that article, she also recommends the book The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance.

I had experimented with keto a couple years prior, but wasn’t able to stick with it for more than a week. Reading Lyn’s article and book recommendation is what made me want to try again, so I did. I transitioned to a strict, well-formulated keto diet in May, emphasizing whole food from quality sources. No ultra-processed keto breads or desserts. Every week I went to my local farmer’s market to buy grass-fed, grass-finished beef from a local ranch, as well as fresh greens, vegetables, and herbs from regenerative farms.

My goal here is to share my subjective, “n of 1” experience with keto, especially in the context of training for and running a long, difficult race. The goal is not to convince you to start eating a low-carb diet. It bugs me whenever I hear people claiming a particular diet is the clearly “the best” for everyone. Food is not a finite game to be won and lorded over other people. Food is information. And besides, nutrition is unsettled science. In my opinion, the human body is an irreducibly complex system3 in the rigorous, mathematical sense, so nutrition will remain unsettled science for a long time. Luckily, I don’t need science to tell me how food makes me feel. I can use my body and intuition as a guide, no science required.

Now, my subjective experience. After the first few days of keto, I felt increased mental clarity and general cognitive “wired-ness” throughout the day. And I started feeling really good at the 6-week mark. At that point, just about every aspect of my life was notably better – sleep, cognition, energy levels, mood. I had significantly less gas and significantly better erections. I had multiple people comment on how good my skin looked and that I looked healthier. When I first experimented with keto a couple years ago, I sensed a difference in how my brain felt after only a couple of days. However, back then I didn’t stay strict with the diet for more than a week, and I didn’t have any of the other benefits that I have experienced this time around at the 6-week mark.

I was also running a lot during this time (see Figure 1), so you may think that all these benefits were from the running instead of the diet. But I didn’t have these benefits when I trained for the 50k last year on a high-carb diet. And it’s been about 7 weeks since the race, and I’ve run maybe 10 miles total, but I still feel the same benefits and am still doing keto.

I started many of my training runs fasted. On the trail I drank water and sugar-free electrolytes and ate high-fat homemade trail-mix containing nuts, MCT oil, basil seeds, and 78% dark chocolate. I added in the dark chocolate after a particularly hot, steep training day when I was squarely in Zone 3 and got dizzy on the uphill climb. I suspect that the rate of gluconeogenesis was not fast enough to prevent hypoglycemia, so my brain started shutting things down. That’s speculation; I don’t have a way of proving it. Adding in a couple grams of sugar seemed to help on the subsequent training days that were particularly hot.

Now that my subjective experience is out of the way, I’m going to share some of the things I’ve learned while researching the ketogenic diet and some its potential benefits for endurance sports. Fair warning: the next section is technical and contains a lot of jargon from nutritional biochemistry. If you don’t care about this, feel free to jump to Race Day where I discuss how the actual race went. If you do care, well, down the rabbit hole we go…

Fundamentals of ATP Production

ATP is the currency of life. If our mitochondria stop making ATP4, we die within seconds. ATP is made from two major metabolic pathways: glycolysis and lipolysis. How do our mitochondria decide which pathway to use? Insulin, mostly5. There are other hormones at play as well, but insulin is the one we can most directly affect through the food we eat. Insulin rises when we eat food with a moderate to high amount of net carbohydrates. Insulin drops when we fast or consistently eat food with a low amount of net carbohydrates. Whenever insulin is consistently low, the first thing our body does is release glucagon, which is a hormone that tells the liver to release its glycogen stores as glucose back into the bloodstream. The problem is the liver can only store about 12 to 24 hours worth of energy in the form of glycogen, depending on your activity level.

So what happens when we are not able to replenish glucose and glucagon through diet? Maybe it’s winter and the berry stock has long been exhausted. Or we live in an Arctic zone where no plant life exists in the first place.

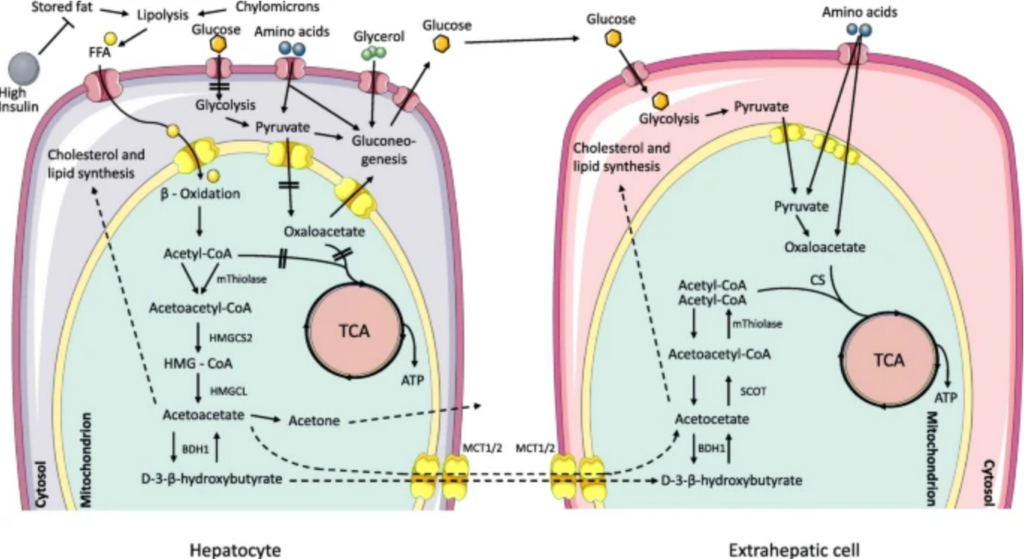

Thankfully we don’t just keel over. Instead, our body starts to leverage the abundant energy stored in fat cells (even a lean person can store around ~20x more energy in fat than they can in their glycogen stores6) through a process called lipolysis. Lipolysis hydrolyzes the triglycerides in our adipose tissue into glycerol and free fatty acids (FFAs). FFAs are carried into the bloodstream and used by most of the cells and organs in our body. The FFAs are converted by β-oxidation to Acetyl-CoA, which then enters the Krebs cycle.

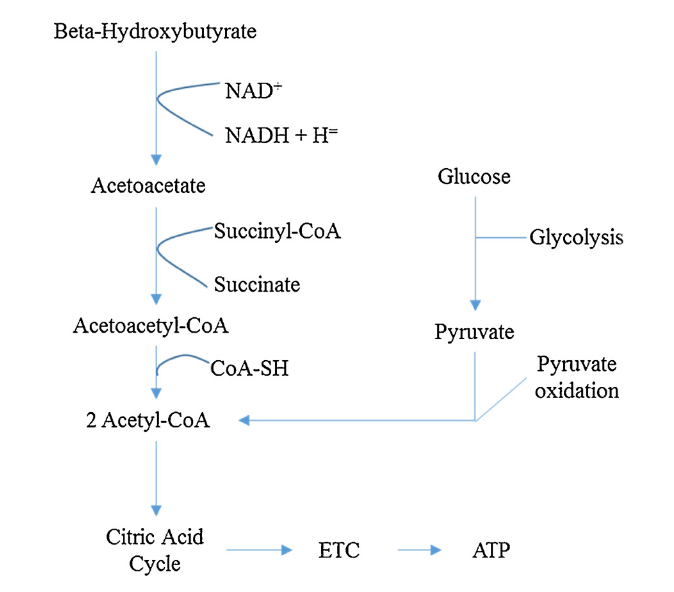

There is one major exception to using FFAs for fuel: the brain. The brain chooses not to oxidize FFAs for ATP7, which is unfortunate, since the brain accounts for around 20% of our basal metabolic demand. As far as I can tell, the reason behind the brain eschewing FFA oxidation is currently unsettled8. So what does the brain use when there isn’t enough glucose and it doesn’t use FFAs? In this case, ATP levels are low, so the ratio of AMP to ATP increases, which activates an enzyme called AMP kinase (AMPK9). In turn, AMPK initiates the process of ketogenesis, the production of ketone bodies in the liver. Ketones enter the bloodstream, eventually reaching the mitochondria in our brain (and other tissues). The receiving mitochondria convert the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (β-OHB) to Acetyl-CoA, giving it another entry point into the Krebs Cycle. Since β-OHB10 is derived from triglycerides, this means our brain and other cells can generate ATP from fat, allowing us to survive for days to weeks to months, depending on how much fat we have stored up.

However, the brain still demands some amount of glucose in the bloodstream, otherwise we become hypoglycemic. That is why if you’ve ever checked your blood when fasted, even if your β-OHB levels are in the 1-3 millimolar range, your glucose will be on the low end of the normal range. How could this be if you haven’t eaten a single carbohydrate in days? The glucose is created from other molecules in the body through gluconeogenesis. Remember the glycerol backbone from the hydrolyzed triglycerides? Gluconeogenesis recycles this glycerol back into glucose. Lactate, pyruvate, and amino acids are other substrates for gluconeogenesis.

A key point to note is that whenever you first start inducing ketosis, it takes time for cells to adapt to the new fuel source. Ketones enter cells via monocarboxylic transporters (MCTs), which are upregulated via AMPK.11 This adaptation can take 4 to 6 weeks to be fully expressed in cell membranes.12

So, we’ve refreshed our memories on ATP production. We know the two primary paths for producing ATP. And we know the basics of ketogenesis. Here’s the question: does ketogenic metabolism provide benefits to endurance athletes relative to glycolytic metabolism?

It’s a tough question. There are many dimensions to ultra endurance running for which benefit could be provided or not. I haven’t attempted to go through all of them. Instead I’ll focus on one area in particular: oxidative stress.

Managing Oxidative Stress

Whenever we exercise, our mitochondria produce large amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are ionic oxygen compounds that increase inflammation, denature surrounding proteins, and cause cellular damage. One of the primary victims of ROS are polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA)13. PUFA are ubiquitous in human tissues and are found in cellular phospholipid membranes14.

The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance proposes that degradation of membrane PUFA by unquenched reactive oxygen species may be a key driver in long recovery times; the more muscle cells that are damaged, the longer it takes to heal. The book estimates that a runner in a 100-mile race would consume roughly 7lbs of oxygen. Assuming a ROS production rate of 2%, there would be around 63 grams of ROS produced over the course of the race. That is enough ROS to degrade 3x the PUFA content in a runner’s legs. The authors also hypothesize that PUFA degradation in the gut could be a cause of the gastrointestinal distress commonly encountered in ultra marathons.

ROS can also inhibit blood flow. Specifically, the enzyme myeloperoxidase (MPO) is abundant in immune cells and generates ROS from H2O215. The MPO in activated immune cells binds with nitric oxide, reducing the bioavailability of nitric oxide to cells in the endothelium16. Nitric oxide is a potent vasodilator, so reducing nitric oxide leads to endothelial dysfunction, vasoconstriction, and poor blood flow (which is probably not something you want during prolonged exercise).

Unfortunately, exercise is not the only source of oxidative stress; ROS is a byproduct of metabolism in general, not just during exercise. And there is evidence that the particular pathway taken to make ATP can greatly influence the amount of oxidative stress.

Glycolysis and Oxidative Stress

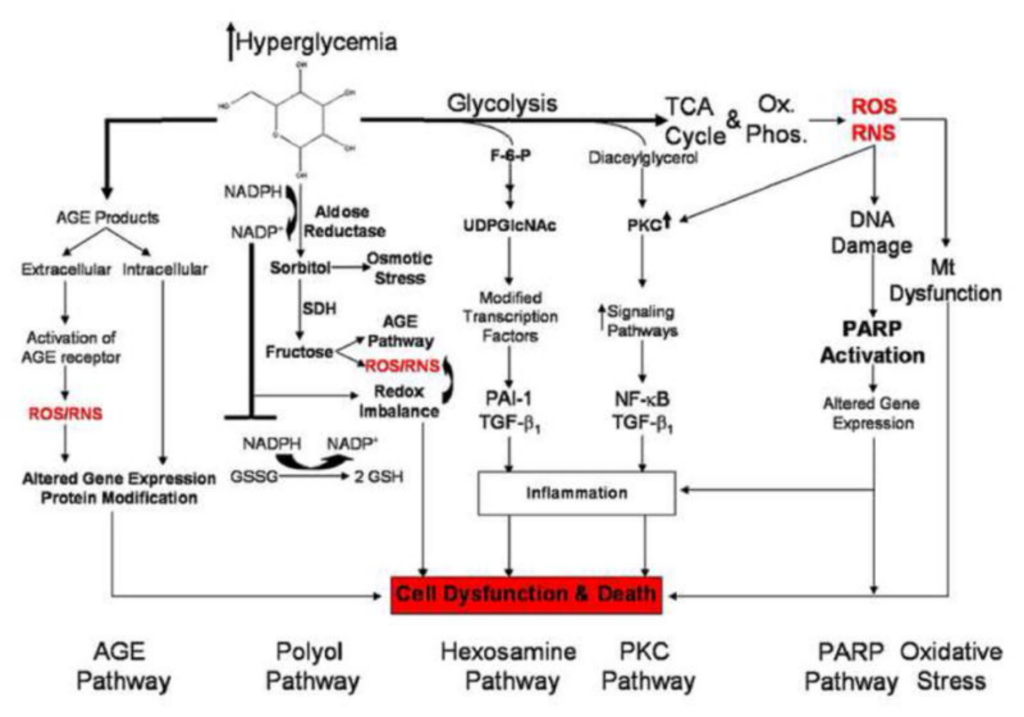

Excessive carbohydrate consumption leads to oxidative stress. Figure 4 below is from a study17 that reviewed various mechanisms of ROS-generating pathways in animal models of hyperglycemia in the context of diabetic neuropathy:

The advanced glycation end-products (AGE) pathway is what you get when you combine high levels of dietary sugar with the proteins and fats in cells18. Glucose and fructose metabolism creates reactive metabolites such as glyoxal and methylglyoxal. These metabolites bond with proteins and lipids, forming AGEs which disrupt the normal function of cells. Methylglyoxal specifically has been shown in animal models to increase oxidative stress through increased production of superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, as well as reduced antioxidant capacity via NADPH depletion in the endothelium, kidneys, and brain19.

AGEs also lead to the expression of a receptor for AGEs (called RAGE) on cell surfaces. RAGE activation is implicated in cardiovascular disease and obesity and also up-regulates nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB)20. Chronic NF-κB activation has been shown to drive a positive feedback loop between pro-inflammatory response and production of ROS, leading to blood vessel and neuronal damage.21

Over-stimulation of the polyol pathway is another source of increased ROS in hyperglycemic conditions. This pathway reduces glucose to fructose (fructose itself produces 7x more AGEs than glucose; methylglyoxal produces 250x more AGEs than glucose) leading to excessive depletion of NADPH. NADPH provides the reducing agents required for regeneration of glutathione, a key antioxidant, which leads to increased levels of unquenched ROS.22

Ketosis and Oxidative Stress

Many keto pundits claim that ketones are a “cleaner burning fuel” than sugar without going into detail on what “cleaner burning” actually means from a metabolic perspective. I did some digging to try to answer this question, and based on what I’ve learned, I think it is reasonable to interpret “cleaner burning fuel” as one that is less prone to reactive oxygen species and inflammation.

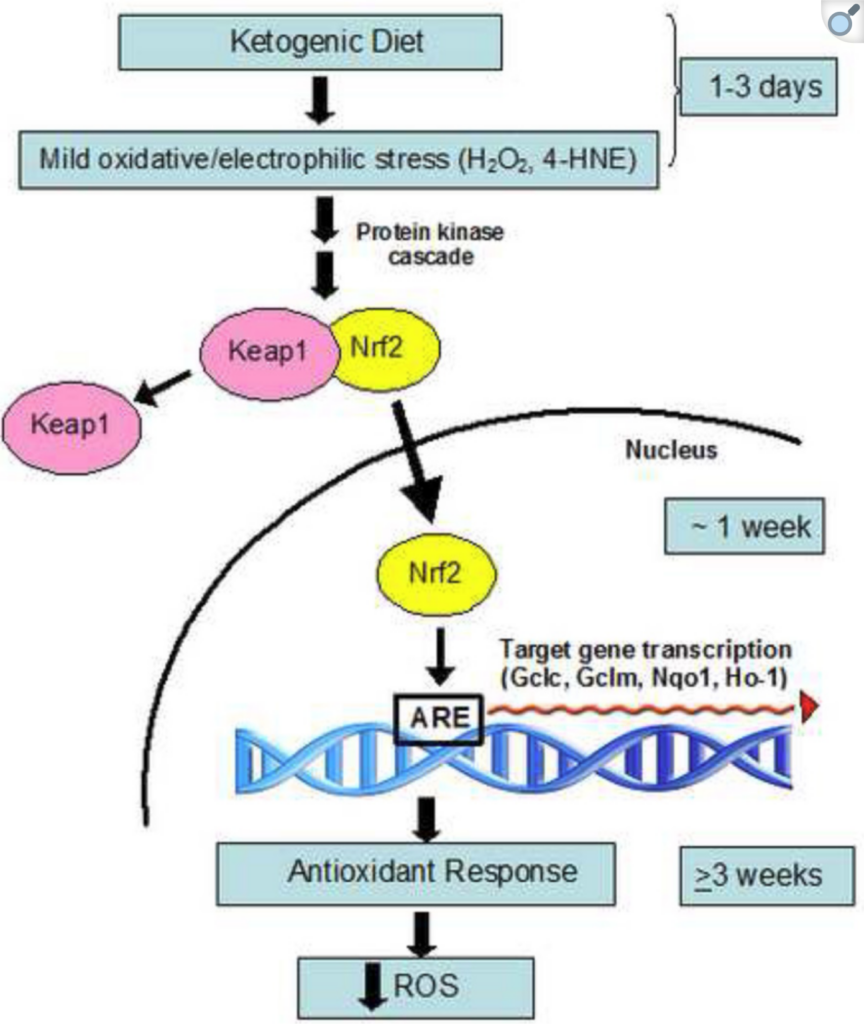

This review by Kolb et al. discusses the interesting possibility of ketone metabolism being initially pro-oxidative stress, followed by a long-term adaptation that is anti-oxidative stress.

It looked at animal studies23 and in-vitro human studies24 that showed increasing acetoacetate, one of three ketone bodies, increased mitochondrial ROS. And increasing both acetoacetate and β-OHB increased NADPH oxidase activity, resulting in less NADPH available for glutathione production. The review then highlights seemingly contradictory studies that show up-regulation of anti-oxidant and anti-inflammatory defenses of ketone bodies. For example25, an (in-vitro human / in-vivo mouse) study showed increased β-OHB lead to increased FOXO3a activity. FOXO3a is a genetic transcription factor that leads to increased expression of antioxidant enzymes: superoxide dismutase 2 (SOD2) and catalase26.

The review resolved this contradiction by analyzing the time allowed for adaptation in each study and found it takes 48 hours to several weeks for the complete expression of anti-oxidant defenses. These defenses include up-regulation of Nrf2 and SIRT3. Nrf2 decreases NF-κB expression, enhances SOD2 activity, and decreases MPO activity, while SIRT3 increases NADPH availability. In simpler terms, after several weeks, inflammation decreased, ROS decreased, and anti-oxidant capacity increased.27

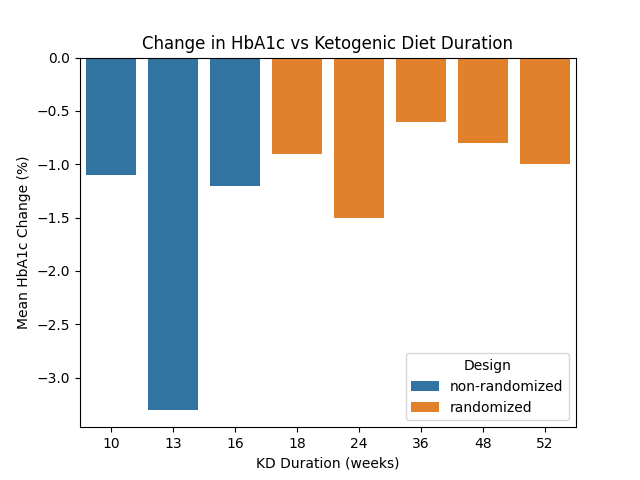

What about those AGEs from glucose and fructose metabolism? We know hyperglycemia contributes to excessive AGE formation, but does this mean that ketogenic metabolism produce less AGEs overall? One place to look is HbA1c, aka glycated hemoglobin. Technically, HbA1c is an early glycation end-product, but Turk et al. showed a significant positive correlation between HbA1c and hemoglobin-related AGEs (Hb-AGE)28 in diabetics. A meta-analysis from 202029 analyzed the effect of the ketogenic diet on HbA1c in humans with type-II diabetes. The analysis spanned 13 studies with a total sample size of n=567 people, and eight of the studies (n=422) measured HbA1c before and after treatment with the ketogenic diet. The plot below shows the average change in HbA1c across the eight studies:

As you can see, each study found a decrease in HbA1c. The average decrease across the eight studies was -1.07%, which is significant, given that a 1% change can mean the difference between normal and diabetic levels according to the ADA. Now there are some limitations to applying these studies to determine if ketogenic metabolism produces fewer glycated end-products relative to glycolytic metabolism. The first is that three of the studies (the blue bars above) had no control group with an alternative diet, so we can’t make a comparison for those cases. The studies also had varying methods to measure adherence to the diet. One had daily β-OHB measurements, another had weekly β-OHB measurements, and one relied on self-reporting of what the participants had eaten. The level of calories also wasn’t controlled for; one was hypocaloric, while others had no caloric restriction at all. Additionally, the type and number of diabetic medications varied across studies and participants. Finally, the sample sizes were small and limited only to type-II diabetics, with the largest study only having 238 participants. Given these limitations, we can’t used these studies to logically conclude that ketogenic diets cause a lower HbA1c relative to high-carb diets. However there does appear to be a correlation, at least in diabetics.

So, in review, we have some evidence that ketogenic diet may reduce oxidative stress through various mechanisms, including down-regulation of inflammation, up-regulation of anti-oxidant defenses, and decreased AGEs. Does this really prove that the ketogenic diet produces less oxidative stress than a high-carb diet? No. First of all, my review effort here was only over a small subset of the research. It was by no means an exhaustive literature review. Second, many of the studies that I did review had uncontrolled, potentially confounding variables that make it impossible to establish causation.

That said, the data at least show some interesting correlations. Enough to make me curious if I would perceive any of these potential benefits throughout my training and the race itself. Subjectively my recovery times on longer (15+ mile) runs were probably around a couple of days, mostly limited by HRV instead of muscle soreness or fatigue. Unfortunately I don’t have a “control” to compare with, since the training was different than the 50k training I did the year before.

Alright, enough from the ketogenic tangent. This post is about the Ouray 50, remember? Next, I’ll describe the race itself and some of the things I learned.

Race Day

My nerves started ramping up about a week out from the race. I didn’t sleep well the entire week. By the time race day finally came, I was both excited and ready to get the damn thing over with. I ate my normal breakfast of bacon and eggs with some coffee and got to Fellin Park around 11AM to check in. The weather was clear with a high of around 73 degrees. This doesn’t seem that hot on paper, but at elevation it was, especially given the first two climbs were on southerly aspects with sparse tree cover.

Fellin Park to Alpine Mine Overlook

The race started at 12PM at Fellin Park in Ouray. The course proceeded south and counterclockwise along the Ouray Perimeter Trail, until it reached the intersection with Camp Bird Rd on the south rim. It then ascends a few miles to Weekhawken trail which leads to Alpine Mine Overlook.

I came out way too fast due to a combination of pent-up anxiety and inexperience. I didn’t have a strict game plan on heart rate or pacing. As you can see from the heart rate data below, I was anaerobic for over three hours at the beginning of the race. Despite this, I felt pretty good going up and down Weehawken. However my body and my mental state took a nosedive as I started the third climb up Hayden Mountain.

Hayden to Crystal Lake

The crux of the race for me was the Hayden ascent. I started up Hayden trail around 2:45PM, the hottest part of the day. I felt dizzy and lightheaded. Luckily, Hayden offered a bit more tree cover relative to Weehawken, especially at the beginning, otherwise I think I would have passed out. I started eating blueberries and my homemade trail mix, but it was too little, too late. At this point, I was struggling to keep my heart below 170, and I had to completely stop roughly 10 times on the way up. The symptoms I felt were similar to the (what I assume was) hypoglycemia on particularly hot training days, but more intense and persistent. About halfway up Hayden, around mile 10, my body refused to swallow any more of the high-fat trail mix I made. It felt as if my brain was shutting down my digestive tract in order to preserve vital organs or something. I didn’t need to vomit, I just literally couldn’t swallow the food.

Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth – Mike Tyson

Suffice it say, I had been punched squarely, unceremoniously, right in the mouth. And it was only mile 10! I hit my mental low. My stream of consciousness was filled with negative self-talk: “How could I have been so stupid to come out so fast? I’ve ruined months of training. I look like a fool! I’m trying to run 50 miles on the keto diet? I can hear the mockery now. My family came all this way, just to see me fail.”

Slowly, I recovered. As I stumbled up the loose, ball-bearing filled switchbacks of Hayden trail, I remembered what I had (serendipitously?) read a few weeks before the race from Man’s Search for Meaning. The meaning of life is not what you get out of life, but what life gets out of you. It’s in how you show up and do the work, especially when it gets hard and you feel like quitting. My mental milieu became a weird mixture of positivity and self-loathing. I decided in that moment that there would be only two outcomes. Either I miss a cutoff and am required to drop, or I finish. There would be no quitting.

I reached Crystal Lake with 20 minutes before cutoff. Crystal Lake was the first aid station that allowed crews and drop bags. My family and friends were there, giving me encouragement to keep pushing. Their presence was energizing. I felt so grateful they were there, that they would take time out of their busy lives to see me voluntarily struggle up and down mountains. One of them got me some bacon to eat, but my body wouldn’t have it. The only things my brain allowed down my throat were fruit, water, and electrolyte pills. And this remained true for the rest of the race. My plan to consume high-fat nutrition had been completely dissolved against the reality of my body. Thankfully I had plenty of fat stores and was 4 months in to fat and ketone adaptation. Now I just needed to get and stay aerobic so I could start mobilizing the fat in volume and spare the residual glucose for the brain.

Crystal Lake to Fellin Park

With about 10 minutes before cutoff, I started back up Hayden trail, this time from the Crystal Lake side towards Fellin Park. I was still moving slow and was near the back of pack, but I felt much better after the short rest at the aid station. It was dusk by the time I got to the black scree at the top of Hayden ridge. By the time I stopped to put my headlamp on, the temperature had dropped about 20 degrees and my heart rate was in zone 2. I started the long descent down Hayden to Fellin Park feeling much better. My mind was clear and I could finally keep a steady pace without blowing up my heart rate.

About a mile away from Fellin Park aid station, there was a small tributary to the Uncompahgre River that crossed the course. I took off my running vest and did a cold plunge for a couple minutes. I could slowly feel my legs getting numb as the icy-cold water flowed over my legs. In that moment, sitting in the freezing water, I was overcome with an intense rush of euphoria and heightened awareness of my connection with Nature. The water on the mountain stripped away my egoic concerns about “racing well” or how others may perceive my sloppy start of the race and replaced it with a quiet, authoritative awareness of the present moment. An appreciation for the harmony of life, for health, for family and friends.

When I finally got to Fellin aid station around 9PM, my crew was waiting there for me. They brought me fruit and warm broth, which I promptly devoured as I sat next to one of the space heaters. I shared my Hayden descent and cold plunge experience with them, and they offered more encouragement. Again, I felt so connected with each of them and grateful for their presence. There was a strange tinge to that moment. Despite having known my family and friends around me for so long, it was as if I was seeing them with a new vibrant clarity. A raw presence that was revealed when the veil of preconceived labels and conditioned mental representations was lifted away from my perception. I’m still curious about what this sensation was and what caused it. It felt as if everything was salient, similar to moving to a new place or the afterglow of a psychedelic trip.

After this commune with fruit and family, I was riding high. The race was halfway over, and I was allowed a pacer for the remaining four sections. Despite there still being 25 miles, I felt the worst was behind me.

The Back Half

Under the cool night sky, the running on the back half was rather steady and uneventful. One foot after another, the miles passed by. Up Twin Peaks via Old Twin Peaks trail, and down to Silvershield with only 10 minutes to spare before cutoff. I arrived back at Fellin Park early Sunday morning, around 1am, and most of my crew were asleep. I ate some more fruit and broth, then picked up another pacer to check off Chief Ouray Mine. Once again back at Fellin, more fruit, more broth. As I was preparing to head out to the final leg up Bridge of Heaven, there were a few racers that crossed the finish line. I was happy for them but also jealous. I wanted to be done. My body felt good, but I was starting to get sleepy and losing mental acuity. However I had done 40 miles and wasn’t about to drop out on the last leg. Cutoff or finish, remember?

The race organizers really saved the best for last when you’re most tired, just to make sure they squeeze every last drop out of you. Bridge of Heaven ascends around 5000 feet over 5 miles, for 10 miles total on the out and back30. My girlfriend paced me. We set out around 5am up the trail. This one was weird because the sun came up about an hour in. The realization that I had been running all night and most of the previous day seemed to place a dense layer of grogginess over my brain. My girlfriend tried to kindle conversation, but the most I could manage in return was short, unthoughtful responses.

Eventually I turned into a metronome. It felt like my body was on autopilot, one foot after the other, driven by some low frequency clock. My mind was essentially absent of all thought for several hours, which is an exceedingly rare state for my psyche to be in. The mind had shed all cares and responsibilities save for the orchestration of my vitals and leg muscles.

Finally, we made it to the top. The last climb was over. After a few minutes of rest and some pictures, we started started the last descent towards the finish at Fellin. The descent involved higher frequency metronome, but was otherwise uneventful. I was exceedingly sleepy and remember longing for one of life’s simple pleasures: sitting in a chair. After about an hour, we were down and headed back towards the finish line at Fellin.

I crossed the finish line with about an hour to spare before cutoff. My family and friends were there to give me hugs and congratulations. After I took some pictures with my new finisher buckle, I finally found a chair in the late morning sun. Sitting in that chair, knowing that I was done, my body and mind began to relax into a state of authoritative fatigue. The kind of fatigue that makes rest non-negotiable. The kind that demands inattention from your environment. I was nodding off in between conversations as the last few runners trickled in through the finish line. Once the podium ceremony was finished, we made our way back to the car. I slept the whole way home.

Reflections

Peaks and valleys. Tension and resolution. Moments of suffering that required me to go within myself and find a way to just keep going. The Ouray 50 was like a small fractal of life itself. It made me thankful for a healthy, resilient body and for a mind that is able to persevere through hard times and to enjoy the good times. The ups and downs of the race gave me a newfound appreciation of the inherent harmony of life. This harmony is ever present in my life, if only I would zoom out from the individual notes and listen to the whole song.

Family and friends. I’m still trying to understand what that “strange tinge” was that I felt when I saw them at Fellin aid station. The feeling that I was seeing them for the first time, and yet loved and cared for them deeply. As if a switch had flipped from cognitive priors to the senses. From predictions based on learned mental representations to a keen awareness of them in that moment. In How to Change Your Mind, Michael Pollan describes a similar phenomenom commonly reported in psychedelic therapy sessions. In Chapter 5, he highlights the theory put forth by Robert Carhart-Harris et al. in their research, The entropic brain: a theory of conscious states informed by neuroimaging research with psychedelic drugs, that different states of consciousness can be placed on a continuum of entropy. States such as anxiety, addiction, depression, and OCD are low entropy states that form deep grooves of cognition, creating a positive feedback loop with themselves. High entropy states, such as the adult brain on psychedelics or the brain of a young child, exhibit increased connectivity and creativity, as well as a diminished sense of separateness from other people and nature. The proposed mechanism behind this theory is an attenuation of the default mode network, or lack of a fully developed one in the case of children, leads to high entropy states. The DMN is believed to be the physical “location” of our sense of self as well as the library of prior experiences, narratives, and labels we use to explain the world. It is believed that reducing DMN activity reduces the sense of self and lifts the veil imposed by the stories we tell about ourselves and others. If this theory is true, could it be that prolonged exercise such as ultra-marathons provide another way to reduce DMN activity? Does ultra-endurance increase the entropy level of the brain? What about other forms of exercise?

Ketosis. Is it optimal for ultra endurance? I don’t know. Maybe if you can stay aerobic the entire time. You probably don’t need to buy those ultra-processed sugary goos and gels that people peddle around. It is safe to say that I didn’t eat 10,573 calories worth of fruit, so the idea that fat can be used as the primary fuel source for ultra events seems to hold up. I am curious about how exactly that happens. The common narrative is that whenever you eat sugar, you spike your insulin, which locks you out of your own fat stores. This must change during exercise in ways that I don’t fully understand. Perhaps the metabolic demand was so great that the residual glucose was immediately taken up by cells and any insulin spike is extremely short lived. I definitely learned the importance of staying aerobic if you’re going to use fat for fuel. I ran the first half of the course a couple weeks before the race for a training run and ate the exact same high-fat trail mix that my body simply refused on race day. During the training run, the trail-mix went down fine, but I also stayed aerobic the entire time. Clearly, going anaerobic for a few hours did not work out so well for me. If I ever run a race like this again, my heart rate will be the key variable I watch, especially at the beginning.

Well, this was a long post. If you’re interested in some further information on low-carb and ketogenic diets, check out the following sources:

- Dr. Peter Attia’s blog31

- Levels blog

- Dr. Casey Mean’s Good Energy

- Dr. Robert Lustig’s Metabolical

As always, thanks for reading.

- It’s actually slightly over 50, but who’s counting really? ↩︎

- For some perspective, the Leadville 100-miler has “only” ~15,700 feet of gain. ↩︎

- Here’s a fun example of complexity and echo chambers: https://www.complexity-explorables.org/explorables/echo-chambers/ ↩︎

- Because we ate a cyanide-laced apple, for example ↩︎

- Reducing metabolism down to one hormone is obviously an immense simplification. ↩︎

- The Art and Science of Low Carbohydrate Performance ↩︎

- This in-vitro study showed that astrocytes from rats were able to oxidize free fatty acids ↩︎

- Romano A. et al, Fats for thoughts: An update on brain fatty acid metabolism, 2017 ↩︎

- AMPK is also activated by metformin, a widely prescribed type II diabetes drug that is thought to have longevity benefits. Perhaps metformin is mimicking a low-carb ketogenic diet? ↩︎

- β-OHB is also a signaling molecule that stimulates the production of SIRT2, which in turn stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis – https://youtu.be/VM8TY_FCm-Y?si=ZDf0z3emYnLtwiVm&t=936 ↩︎

- M Felmlee et al., Monocarboxylate Transporters (SLC16): Function, Regulation, and Role in Health and Disease, 2020 ↩︎

- Barry D. et al., The ketogenic diet in disease and development, 2018 ↩︎

- Ho E. et al. Biological markers of oxidative stress: Applications to cardiovascular research and practice, 2013 ↩︎

- Kumar S.D. Kothapalli, Hui Gyu Park, Niharika S.L. Kothapalli, J. Thomas Brenna, FADS2 function at the major cancer hotspot 11q13 locus alters fatty acid metabolism in cancer, Progress in Lipid Research, Volume 92, 2023 ↩︎

- Ho E. et al. Biological markers of oxidative stress: Applications to cardiovascular research and practice, 2013 ↩︎

- Abu-Soud H. and Hazen S., Nitric Oxide Modulates the Catalytic Activity of Myeloperoxidase, 2000 ↩︎

- Figueroa-Romero C. et al., Mechanisms of disease: the oxidative stress theory of diabetic neuropathy ↩︎

- See also: Maillard Reaction ↩︎

- Matafome, P., Rodrigues, T., Sena, C., & Seiça, R. (2016). Methylglyoxal in Metabolic Disorders: Facts, Myths, and Promises. Medicinal Research Reviews, 37(2), 368–403. doi:10.1002/med.2141 ↩︎

- Figueroa-Romero C. et al., Mechanisms of disease: the oxidative stress theory of diabetic neuropathy ↩︎

- Kawamura, N. Inflammatory mediators in diabetic and non-diabetic lumbosacral radiculoplexus neuropathy, 2007 ↩︎

- Figueroa-Romero C. et al., Mechanisms of disease: the oxidative stress theory of diabetic neuropathy ↩︎

- Abdelmegeed M. et al., Acetoacetate Activation of Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase 1/2 and p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase in Primary Cultured Rat Hepatocytes: Role of Oxidative

Stress, 2004 ↩︎ - Jain, S K. et al., Ketosis (acetoacetate) can generate oxygen

radicals and cause increased lipid peroxidation and growth inhibition in

human endothelial cells, 1998 ↩︎ - This is an example of β-OHB acting as a signaling molecule for the epigenome. It is more than just an alternative fuel source. ↩︎

- Shimazu T. et al., Suppression of Oxidative Stress by β-Hydroxybutyrate, an Endogenous Histone Deacetylase Inhibitor, 2012 ↩︎

- Kolb, H. et al., Ketone bodies: from enemy to friend and guardian angel, 2021 ↩︎

- Turk Z. et al., Comparison of advanced glycation endproducts on haemoglobin (Hb-AGE) and haemoglobin A1c for the assessment of diabetic control, 1998 ↩︎

- Yuan X. et al., Effect of the ketogenic diet on glycemic control,insulin resistance, and lipid metabolism in patientswith T2DM: a systematic review and meta-analysis, 2020 ↩︎

- Fun fact: the summit of Bridge of Heaven links up to the north end of Bear Creek National Recreation Trail. The Bear Creek to Bridge of Heaven loop was one of my favorite and most difficult training runs ↩︎

- For a deep dive on the organic chemistry of ketone bodies and ketosis, start with this series of posts: https://peterattiamd.com/ketosis-advantaged-or-misunderstood-state-part-i/ ↩︎