What do tariffs and the meteoric rise of Oliver Anthony have in common? One is a sledgehammer that the Trump administration is hell-bent in swinging to reorder global trade; the other is a country music star with a message dripping in populism.

My aim is to show that both of these phenomena, while very different on the surface, are inextricable nth order effects of the same root cause. The root cause is something that the majority of Americans either take for granted or are completely ignorant to: the US dollar’s status as the global reserve currency and the debt-based fiat monetary system on which this status depends. An nth order effect is, simply put, a consequence of some event. The set of these effects for a given event is constructed by repeatedly asking the question “And then what?”. If I eat candy every day, the first order effect is a rush of pleasure and dopamine. The second order effect is stomach distress and low energy. A third order effect is diabetes. Many people (myself included) sometimes fail to look beyond the first order effects of decisions they make and of events they become aware of. This leads to a shallow understanding of events that occur within complex systems and an under-appreciation of potential future outcomes.

The Trump administration wants to balance the United States’ long-standing trade deficit. To achieve this policy goal, Trump is levying tariffs on trade partners in order to encourage the re-shoring and revitalization of the US industrial base. However, in my view, tariffs alone will be ineffective in balancing trade in the long run, because the trade deficit is an nth order effect of the true root cause: the US dollar status as global reserve currency and the debt-based fiat monetary system. Tariffs do nothing to address this root cause, and in fact, Trump has emphasized the administration’s official policy is to preserve the US dollar’s reserve currency status. However, just because tariffs alone may be ineffective, doesn’t necessarily mean the underlying policy objective shouldn’t be pursued.

The aim of this post is not a political one, but rather to analyze the tariff policy within the reality of the economic system it is being deployed in so that we can make informed judgements of its efficacy and worth. To this end, we will start with a brief history of the modern dollar system and the elevation of the dollar to global reserve status. Then we will see how this system is linked to persistent US trade deficits. Once we understand this financial plumbing, we can make an informed judgement on whether tariffs alone are likely to be effective. In order to judge whether the underlying policy (i.e. balanced trade) is worthwhile, we will look to various other consequences of the current system and the impact it has had on the American public, including the recent wave of political populism and general feeling that the American dream is out of reach for many people. With these effects correctly attributed to the root cause, which transcends political divisions, we can develop a more nuanced view of the underlying goal of balanced trade, even if we may disagree with the means to achieve it.

A quick aside: much of my view has been influenced by Lyn Alden and her book Broken Money, as well as work from macroeconomists Luke Gromen, John Mauldin, @infraa_. I recommend checking out their stuff for a further deep dive.

The Rise of King Dollar

At the peak of World War II, Allied financiers and central bankers convened in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire to create a new global monetary order to be enacted once the war was over. At this point in July of 1944, the United States had emerged as the country best positioned for imposing a new international financial system on the rest of the world. The US had built up an immense manufacturing capacity and the American homeland had avoided the devastating damage that plagued Europe, Asia, and the Soviet Union.

The so-called “Bretton Woods system” would confer the lofty status of global reserve currency to the United States dollar. Under Bretton Woods, member nations agreed to maintain a fixed exchange rate against the dollar, while the dollar itself was redeemable for gold at $35 per ounce. The intent of this system was to facilitate free international trade using the dollar as the common medium of exchange.

There was a problem though. In order for nations to settle trade in dollars with each other, they needed dollars. But dollars only come from the United States. Foreign nations and companies cannot create more dollars themselves, and Europe, Asia, and the Soviet Union had very little export capacity relative to the United States due to the physical destruction from the war, i.e., they had very little to sell in exchange for dollars.

At the very beginning of Bretton Woods, the United States had what is called a balance of payments surplus. You can think of a country’s balance of payments as a record of all the value flowing into and out of the country. A surplus means that more value is flowing in than is flowing out. The balance of payments includes things like the trade balance and the financial account. The US was running huge trade surpluses and had amassed sizeable dollar reserves. This surplus had to be reversed in order to supply the rest of the world with dollars that it needed. It did this initially through grants and loans, since the European export capacity was severely hamstrung at the time.

This deliberate outflow of dollars was bootstrapped by massive aid packages such as the Marshall Plan, during which the US gave Western European countries approximately $17 billion to jumpstart re-industrialization. About 90% of the Marshall Plan aid was given in the form of grants rather than loans, for which Europe didn’t have to pay the United States back. This injection of dollars helped spur European industrial capacity, and by the end of the Marshall Plan in 1952, European exports had doubled, and industrial output had increased 55%.

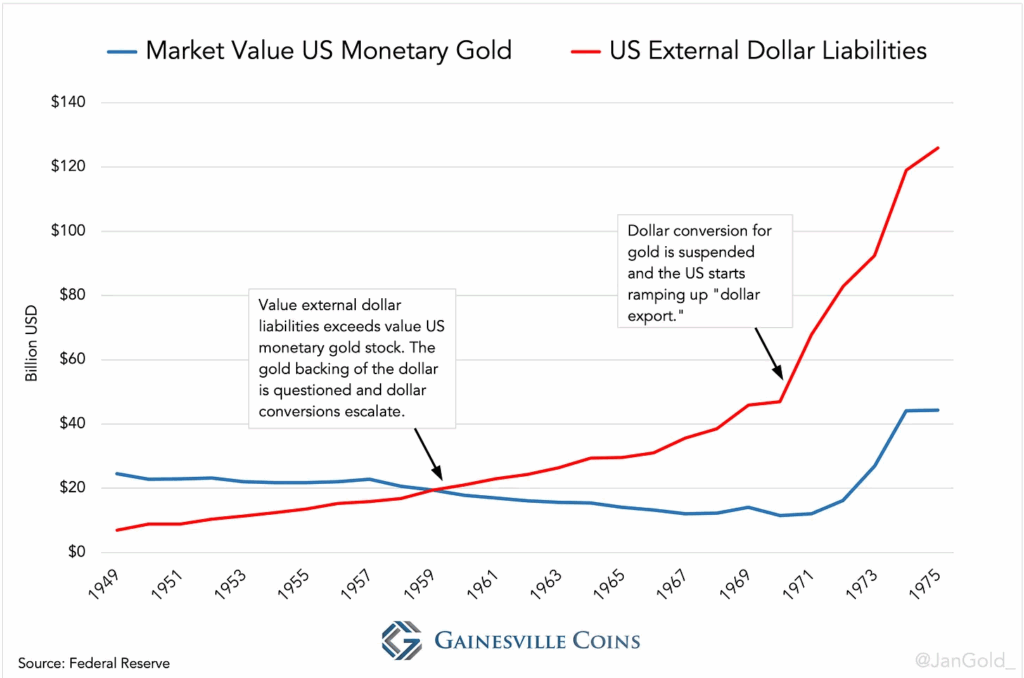

These persistent balance of payments deficits, i.e., export of dollars, and the impetus to use dollars for global trade by non-US countries, created what is called the Eurodollar market. Despite the name, the Eurodollar market is the market for dollars between any nation that is not the US, not just in Europe. The Eurodollar market experienced dramatic growth during the 1960s. It grew from $75 billion to $264 billion (in 2020 dollars) between 1964 to 1969. Keep in mind that each dollar deposit in a foreign country ultimately represents a liability of the United States, since every dollar was redeemable for gold by foreign governments and their central banks.

As seen above, eventually the level of external dollar liabilities exceeded the value of the US gold supply. This coincided with large inflationary deficit spending by the United States in the late 1960s in order to fund the Vietnam War and President Johnson’s Great Society. The deficit increased 5x during this period, from $5.9 billion in 1964 to $25.2 billion in 1968.

There are a couple of reasons why the foreign (Eurodollar) and domestic liabilities were able to grow so quickly under Bretton Woods.

The first dates back to three decades earlier, when FDR declared an emergency bank “holiday” and signed a series of executive orders during the 1933 banking crisis. Executive Order 6102 made ownership of over $100 worth of gold in the form of currency illegal for US citizens. Executive Order 6073 ended the domestic convertibility of dollars for gold at US banks. Later that year in June, Congress revoked the “gold clause”, which nullified any obligations for settling private and federal contracts in gold. Finally, in 1934, the Gold Reserve Act enabled the President to perform a de jure devaluation of the dollar by adjusting the gold peg from $20.67 to $35 per ounce. These policies amounted to confiscation of gold from the American public into the Federal Reserve system and marked the end of the gold standard domestically.

At the same time gold flowed into the Fed from private citizens in the 1930s, the required gold reserve ratio decreased throughout the Bretton Woods period. From the establishment of the Fed in 1913 through 1945, the Fed and its member banks were legally required to maintain a 40% gold reserve. This was reduced to 25% in 1945, and to 0% in 1968. The net effect was the US banking system was no longer constrained by their gold levels and could create loans based on fiat dollar reserves rather than physical gold reserves. This leads us to the second reason for the huge expansion of dollar liabilities under Bretton Woods: fractional reserve lending.

Fractional reserve lending allows banks to create new money in the form of loans while only keeping a small percentage of the initial deposit as physical reserves1. Assuming all banks have a reserve ratio of 10%, if you deposit $100 into the bank, the bank will loan out $90 of that deposit to a borrower while earning the spread between the interest it pays you and the interest is charges the borrower. That $90 then gets loaned again by another bank with a 10% reserve ratio, resulting in $81 for the new loan. This process tends to continue via the profit motive for banks to earn the interest spread between deposits and loans. If you do the math, the amount of new money created from this process (aka broad money), works out to be equal to: initial deposit * (1 / reserve ratio). So a $100 deposit with a 10% reserve ratio results in $1000 of new broad money created on top of the $100 base money2. This is why base money, like actual physical currency and checking accounts, is referred to as “high powered money”; it has a multiplicative effect on the overall supply of broad money in the system.

So you can see how the end of domestic gold convertibility combined with fractional reserve lending lead to enormous sums of new broad money creation. This money creation process accelerated under Bretton Woods as the United States began exporting dollars to the rest of the world, and the Eurodollar market began to metastasize. These offshore US dollars were also expanded using fractional reserves as industrial capacity came online in Europe.

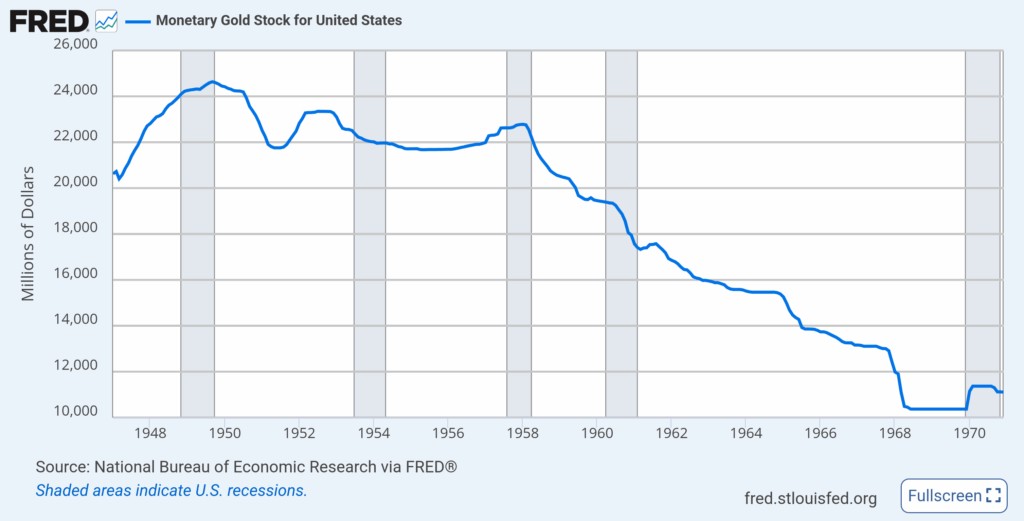

Eventually Western European nations sniffed out the unsustainability of this system. There were simply way to many dollars and not enough gold in the US. The suspension of the gold standard in the 1930s only applied to citizens and banks within the country. Foreign governments and their central banks were still able to redeem their dollars for gold. So that is exactly what they did. Nations like France and Germany began draining gold from the US in order to evade the monetary debasement that was occurring in the dollar:

This run on the United States’ gold stock was so acute in the late 1960s that it prompted the so-called “Nixon shock”. In 1971, President Nixon announced that the US would no longer allow foreign governments to redeem dollars for gold, ending the gold standard completely. The Nixon shock was effectively a default by the United States and marked the end of the Bretton Woods regime.

The Dollar and Trade(offs)

The collapse of Bretton Woods was predicted in 1959 by an economist named Robert Triffin. Triffin identified a contradiction, called Triffin’s dilemma, inherent to the system: in order for the rest of the world to use the dollar in international trade, foreign countries must have dollars. These countries can’t print dollars, so they have to get the dollars through continuous US trade deficits (or more generally, balance of payments deficits, which includes things like foreign aid as in the Marshall Plan). Trade deficits provide foreign countries with the surplus dollars needed to settle trade.

Now the problem isn’t really with the occasional trade deficit. In a normal scenario, the excess supply of the currency from the deficit will put downward valuation pressure on it relative to other currencies. This devaluation causes the country’s exports to become more competitive on a relative basis. As exports become more competitive, the trade deficit turns into a balance or even a surplus.

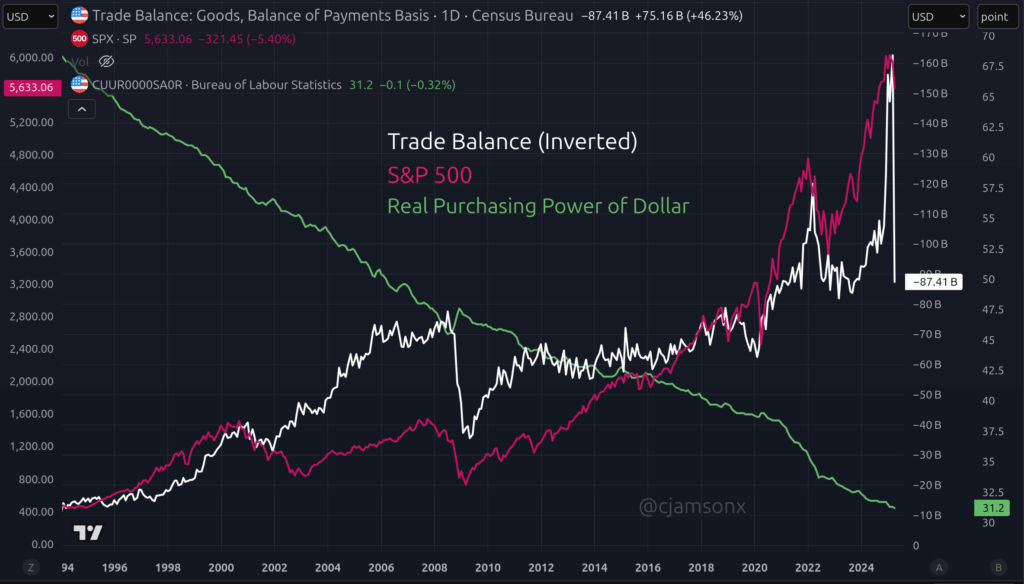

However, when the country (US) maintains the world reserve currency (dollar), this natural equilibrium is never reached. The excess supply is soaked up by the global demand, keeping the relative value of the dollar propped up. The key word here is relative. On a relative basis, the dollar is strong, however in absolute real terms, the dollar gets much weaker over time. The one-two punch of abandoning the gold standard and the proliferation of debt through fractional reserve lending leads to massive loss of purchasing power for holders of US dollars over the course of decades. This weakness, as starkly demonstrated in the graph below, undermines the collective belief that the dollar is worthy as being the global reserve currency.

Triffin’s dilemma captures the dynamic between the global reserve currency and trade deficits that I think Trump doesn’t fully understand or at least doesn’t appreciate. The deficits are a consequence of the US dollar’s global reserve currency status. They don’t just happen randomly or because of mercantilist policies from China. Sure China’s policies such as the intentional devaluation of the yuan may exacerbate the deficit, but these effects are marginal relative to the structural flows that result from the dollar reserve status.

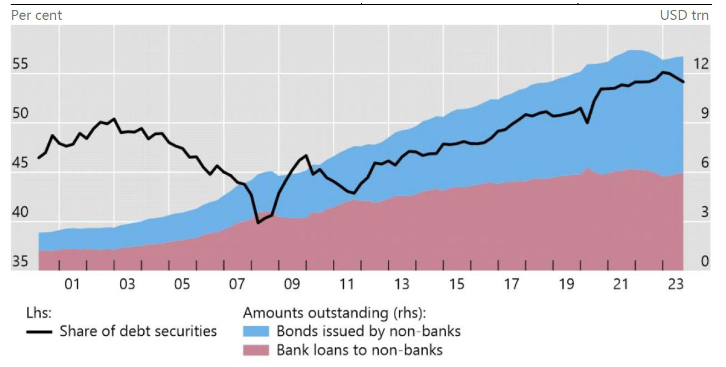

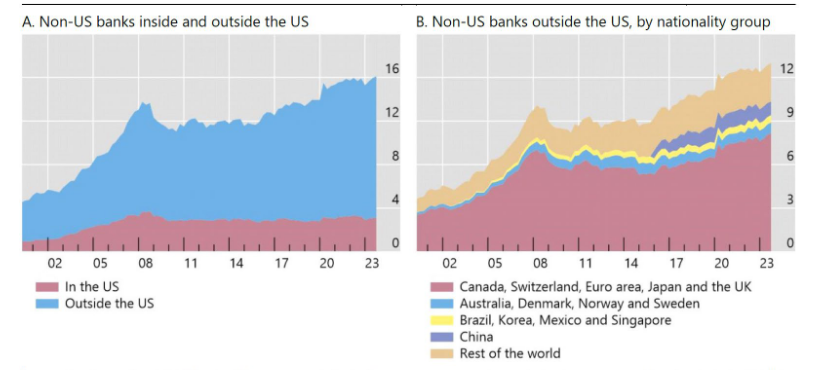

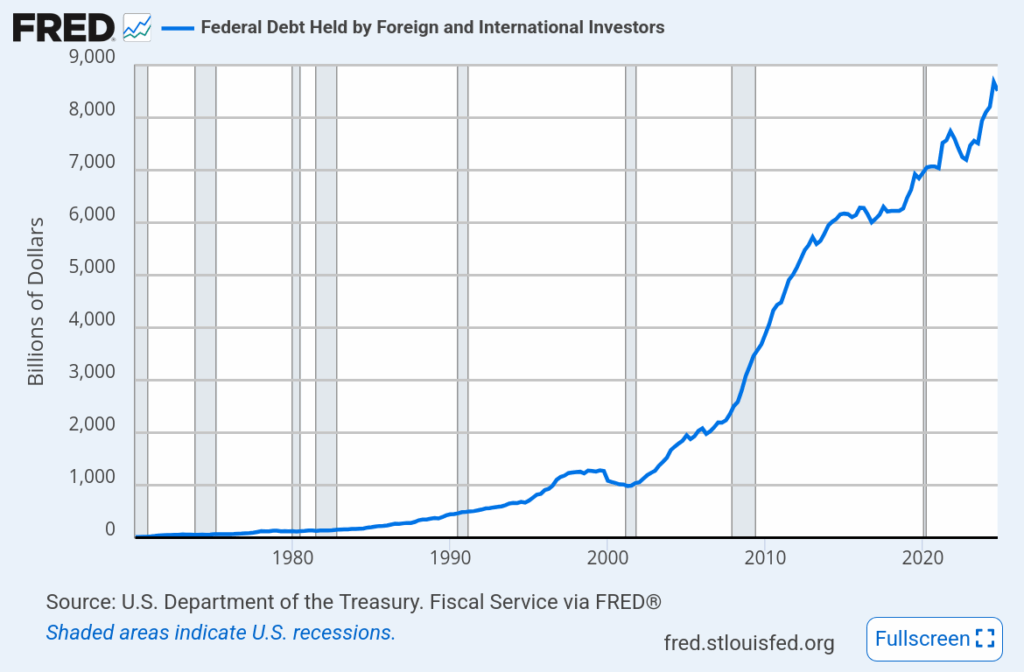

Any meaningful tariff increases have little staying power, because they do nothing to address the root cause of the deficits in the first place. The bottom line is that dollars must continue to flow to the rest of the world. The reason is that there have been trillions of dollars worth of debt that has accumulated outside the US over the past several decades, where neither the creditor nor the debtor are US-based entities. These so-called “offshore” debts are between foreign corporations, households, banks, and governments. The charts below from the Atlanta Fed show the magnitude of these liabilities to be in the tens of trillions:

Except for the roughly $3T in the bottom left graph, all of these liabilities are held outside the United States. The interest payments on these debts create inelastic demand for US dollars. When trade is free-flowing, the dollar income can be used to make the interest payments, no problem. But if trade income falls due to massive tariffs (or other shocks like COVID-era supply chain disruptions), dollars have to be sourced from somewhere else.

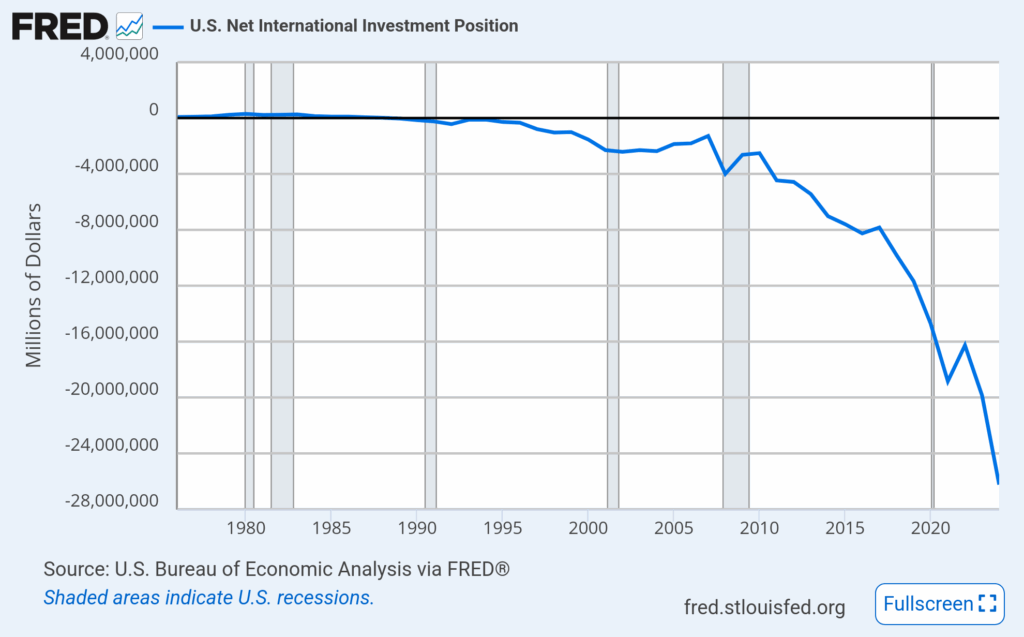

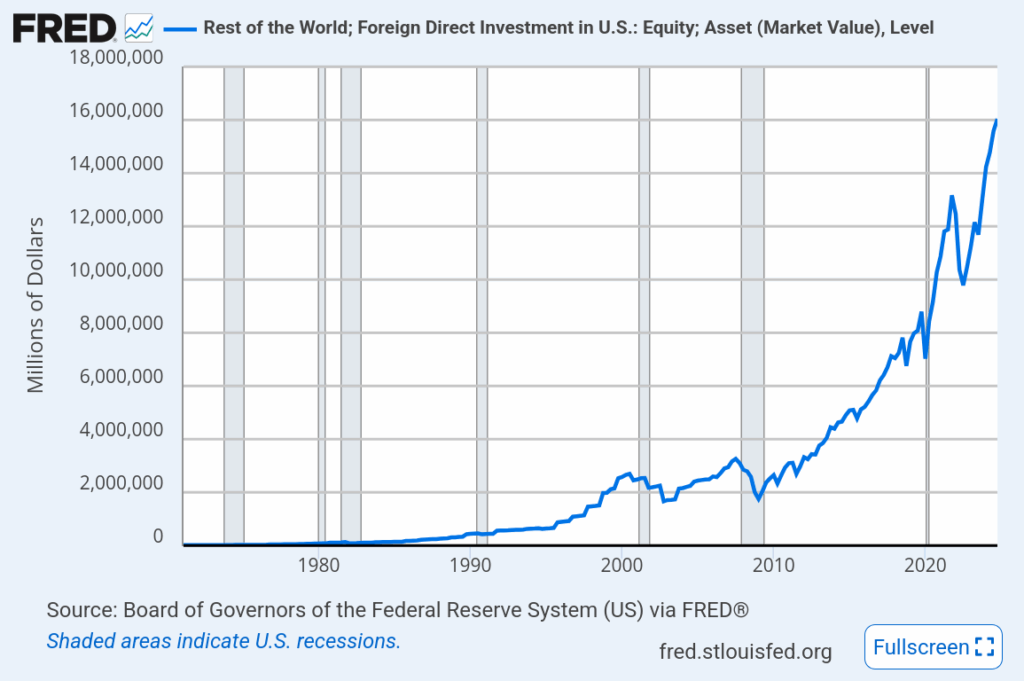

Where do the dollars come from in the absence of trade? Liquid US assets, mainly stocks and bonds3. When countries run a trade surplus with the US, they reinvest much of their dollar profits back into the shares of US companies and US government debt. The degree of this foreign ownership of US assets is captured in the United States’ net international investment position (NIIP). A negative NIIP means that foreign countries own more American assets than America owns of foreign assets. We can also look directly at foreign investment in US equity and debt markets. The graphs below illustrate growth of this foreign ownership of US assets over the past few decades:

So whenever countries experience a dollar shortage due to severely reduced trade, they can sell their US assets in order to raise cash. This cash can then be used to service their dollar denominated debts. This is one of the reasons why US stock and bond markets sold off after Trump’s Liberation day in April. Typically US Treasuries are considered safe-haven assets, resulting in a bid (yields going down) whenever there is risk-off sentiment in the market. But yields didn’t go down after Liberation Day. The went up. Which means bonds sold off hard.

The bond market is another reason why meaningful tariffs have no real staying power. Foreigners own upwards of $9T worth of our debt which they can and will sell if they are forced to raise dollars to meet their interest obligations4. They can also sell Treasuries to create upward pressure on interest rates, which can have serious consequences for the global monetary system. It is not a coincidence that the Trump administration quickly walked back from the reciprocal tariffs and the 145% China tariff after the sharp bond market sell-off. Bessent made it clear, they don’t really give a shit about stocks. But they absolutely care about the bond market.

The US Treasury market is the foundation of the global financial system, so any prolonged disorderliness in that market has catastrophic implications. Think of it this way. The entire dollar system is like a massive game of musical chairs, with 10,000 people to every one chair. The ever-increasing debt that flows from the Treasury market is the music. If the music ever stops, the game is over because the system is completely insolvent. The thing is, the rest of the world knows this. For this reason, their ownership of US debt offers them immense leverage at the tariff negotiating table, much more than the Trump administration is probably willing to admit publicly.

My view is that tariffs are more likely being used as negotiating leverage rather than sustainable long-term policy. I think when the dust settles we will see some tariffs on the margin for specific strategic goods (steel, aluminum) and industries (artificial intelligence, semiconductors, pharmaceuticals). Along with some sort of “Mar-a-Lago Accord” that results in a globally coordinated weakening of the dollar relative to its peers, similar to the Plaza Accord in the 1980s. Steve Miran, Trump’s chair of the Council of Economic Advisors, proposed this as a possibility in his recent paper A User’s Guide to Restructuring the Global Trading System. That paper is long but worth it if you want deeper insight into the ideas behind the administration’s policy. To that end, the dollar has already lost about 10% since Inauguration Day. This is positive for the Trump administration’s goals, as it makes US exports more competitive.

A Damn Shame

Despite my view that broad reciprocal tariffs are basically not possible for any prolonged period of time due to the structural demand for dollars, I do think the underlying goal of restoring relative prosperity to the American middle class is vitally important. The current system has left many Americans disillusioned with the social contract they were raised to believe, which is that hard work pays off.

In the last 50 years, the United States has exported dollars and its manufacturing base overseas. As discussed above, this has created a strong network effect of dollar-based trade, leading to a persistently strong dollar and massive inflows of capital back into US debt and equity markets. The question is whether this is good for America or not. The answer is it depends on which American you ask. If you ask someone that owns stocks or real estate, they are probably OK with the status quo. According to the latest FRED data from the St. Louis Fed, the top 1% wealthiest Americans own 34% of all financial assets, whereas the 50th wealth percentile owns just 2.6%. The majority of Americans that live purely off of wages have missed out on the enormous nominal wealth that has accrued to asset owners.

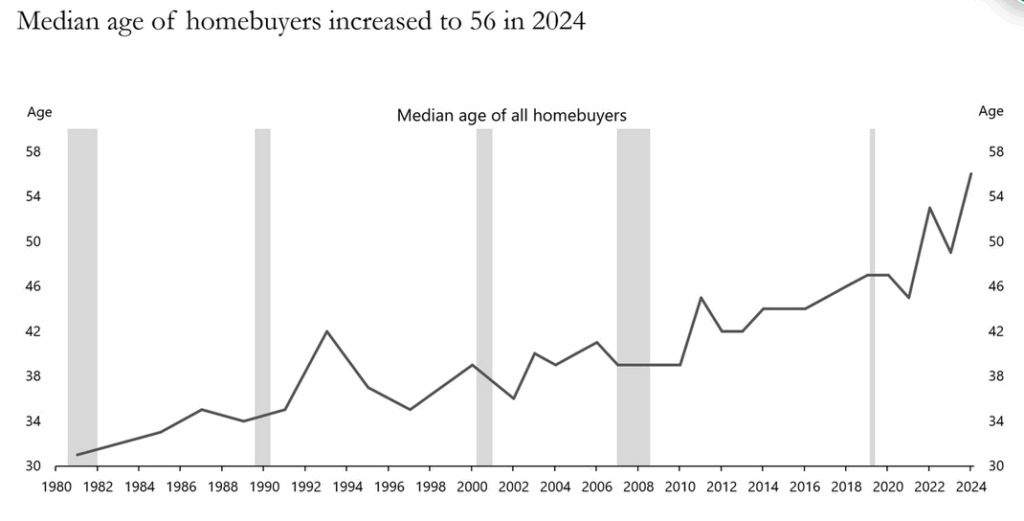

The sense of falling behind is reflected in the actual data for major life milestones such as buying a home and having kids. The following chart from Apollo Chief Economist Torsten Slok shows the median age of all homebuyers is at an all time high of 56 years old:

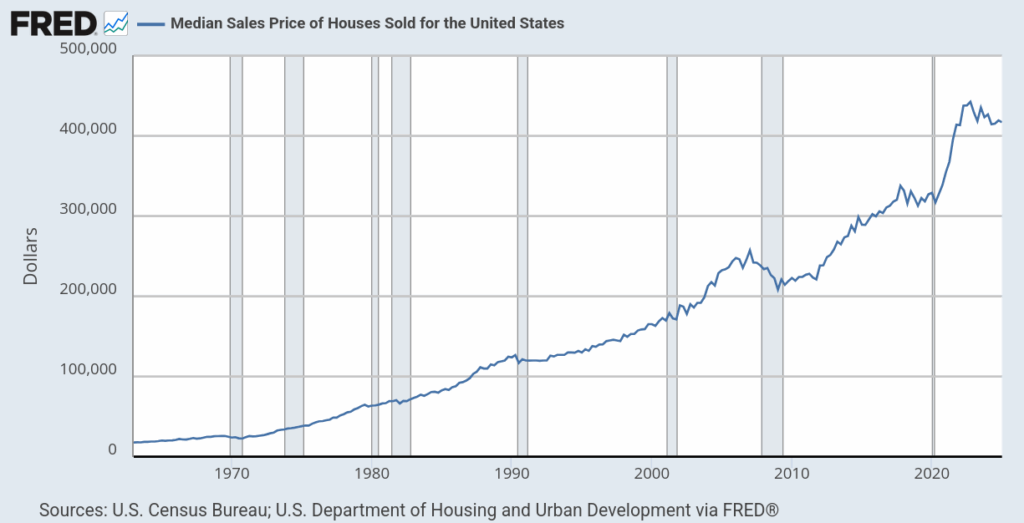

This tracks with the increase in the median sales price of houses sold over a similar period:

Have you ever wondered why housing prices have increased so much in price? A 3-bed 2-bath today is not that physically different from what it was 40 years ago, let alone 5 years ago. Yet home prices have increased 33% since COVID. One reason is that homes these days are used more than just for shelter. They are investments and a means to store value, i.e., they carry a “monetary premium” on top of their value for shelter. Most mortgages these days are bundled up into a fixed income instrument called a mortgage-backed security (MBS). Each MBS is sold by Wall Street to various institutional investment firms like pensions and insurance companies. These are exactly the same financial instrument that caused the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. In the time since that crisis, the Federal Reserve has printed trillions of dollars to directly buy MBS as part of their quantitative easing programs, in effect subsidizing the mortgage market with money created out of thin air. This “financialization” of the housing market has kept rates low and allowed for large institutional buyers and private equity firms like Blackstone to acquire massive portfolios of single family homes, pricing out the average American family.

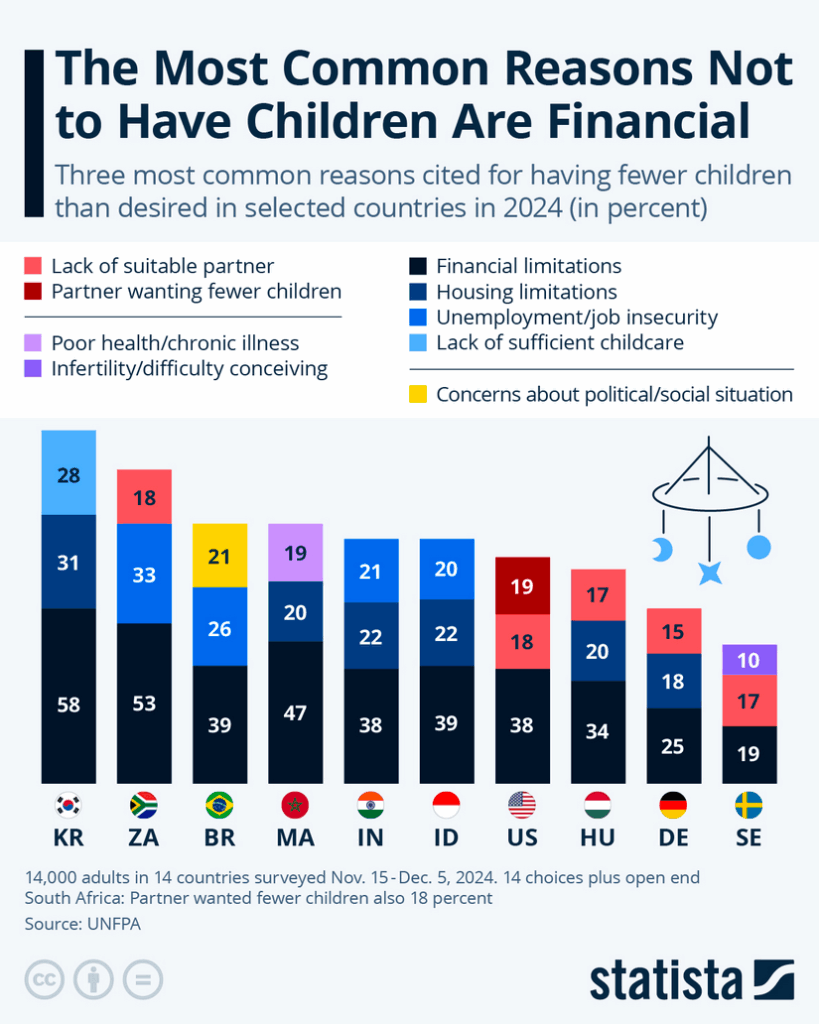

People are having fewer kids as well. The birth rate in the US has fallen from over three births per woman in the 1960s to around 1.6 births per woman today. Statista recently reported a new survey that showed the most common reason cited for not having kids was financial limitations:

This game of hyper-financialization has been playing out for decades now. You can either choose to play or not. If you don’t, you are aren’t going to keep up in nominal (monetary) wealth terms unless you have an inheritance. If you do decide to play, you have to invest time and money just to keep up with inflation, let alone to grow your wealth in real terms. The system of endless debt turns every dollar into an ice cube on hot pavement. Or, in the words of Oliver Anthony, “your dollar ain’t shit”. Case in point, the dollar has lost 25% of its value since 2020 due to the massive fiscal and monetary stimulus response to COVID.

What is the impact of this financial game that is so clearly rigged against the majority of the American public?

Show me the incentives and I’ll show you the outcome.

– Charlie Munger

Populist songs like Rich Men North of Richmond. OnlyFans. Assassination of elites. The Red Wave. Online gambling and 0DTE options. When people struggle to afford basic necessities like food, the social fabric starts to unwind5. Violent protests and riots start to become every day news. Many people blame politics (specifically the sitting president) for these things, and I agree that they play an important role. But the problem with our money is bipartisan; the graphs above span decades and multiple administrations, both Democrat and Republican. Tariffs may have some effect around the margin to bring specific industry back to American soil, but they will do nothing to reverse the profligate debt expansion that the current system depends on and the devastating consequences this expansion has on the value of the dollar and the American people.

What is the solution, if not tariffs? It’s a really tough question; one that I don’t have a full answer to. I think any solution has to address the root cause: the dollar as global reserve currency and the fiat financial system we have today. Replacing the dollar for a neutral reserve currency would allow for the US trade balance to reach a natural equilibrium. This transition back to a net-positive or net-zero trade regime would be painful initially, as it would require the US to consume less than it produces for some time. This would require a massive cultural shift in behavior, values, and norms, but it is possible to do. If we were to replace the debt-based system with one based on credit and hard money (i.e. money that cannot be debased), it would flip the underlying price dynamic from an inflationary one to a deflationary one. Imagine the price of eggs falling each year rather than rising. Mainstream economic thought would say this situation is bad because if people expect prices to fall, they will tend to hoard the currency rather than spend it, causing the economy to grind to a halt6. I agree that massive deflation probably is not good, but why not 1% per year? It would align with the naturally deflationary force of technology, which is only going to accelerate in the coming years due to AI and robotics. Call me crazy, but gradually falling prices and robots doing my laundry and getting me groceries sounds like peak human civilization to me :).

Thanks for reading,

Connor

- Like cash in a vault or deposits at the Federal Reserve ↩︎

- The required reserve ratio has been…drumroll…0% since the COVID crash in 2020. This means the money multiplier is 1 / 0, which is a very big number. ↩︎

- This isn’t the only alternative source. In periods of severe market distress, the Fed steps in to supply dollars via swap lines, which are short-term dollar loans made at the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR). ↩︎

- There is likely much more nuance than described briefly here. The elephant in the US Treasury room is the insane multi-trillion dollar deficits that the US government is running, and only plan to grow with passage of things like the Big Beautiful Bill which is estimated to increase the deficit by $2.4 trillion over the next ten years (excluding interest cost!). The bond market is demanding higher rates to compensate for the inflationary nature of DC’s spending addiction and the potential inflationary impact of increased tariffs. ↩︎

- See the Fall of the Roman and Weimar Republics. ↩︎

- This is what made the Great Depression so nasty ↩︎